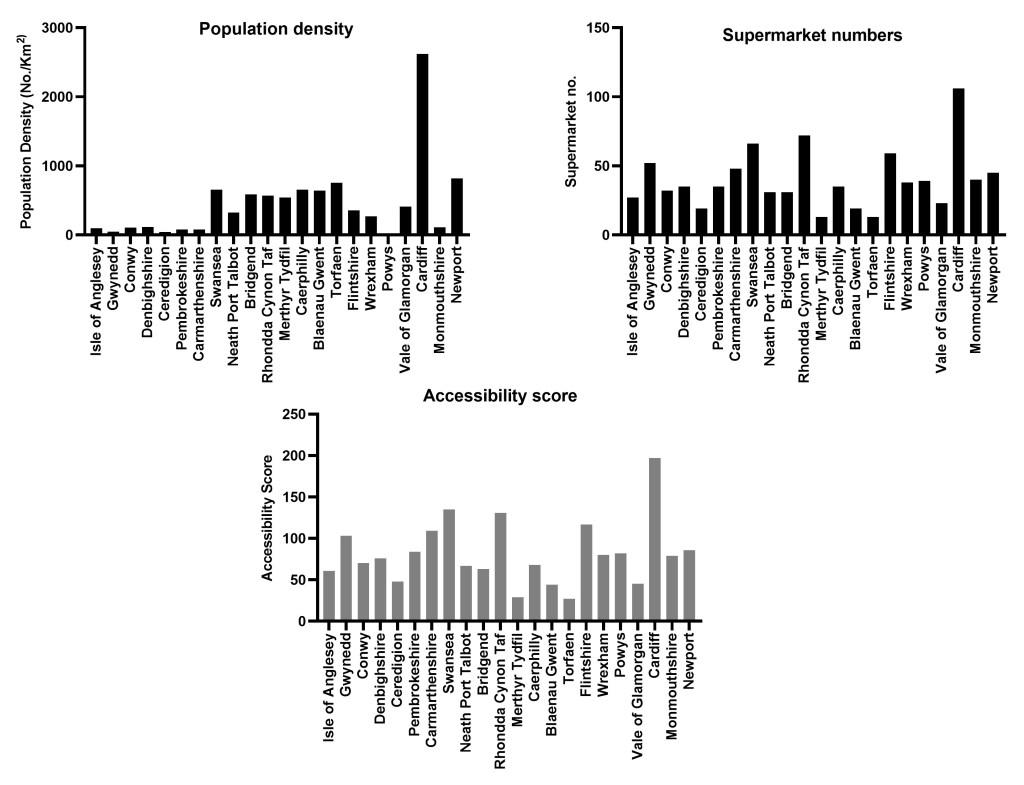

Research I carried out in 2022 looked at how accessible a healthy diet is in Wales, one of the factors influencing poor quality of diet is thought to be the increased likelihood of deprived areas being ‘food deserts’ defined as those areas with decreased accessibility to healthy food and less supermarkets, both risk factors for food poverty [1].

Within this study the number of supermarkets present within each region of Wales was compiled along with size of the store, small supermarkets are present in the highest numbers across Wales but are not able to supply the range of product choice and competitive pricing that larger retailers can offer [2].

In order to measure accessibility an ‘Accessibility Score’ was used to rank the regions of Wales by combining a ratio of supermarket frequency: population density (No./Km2) with a supermarket quality score according to store size (Small < 280M2, Medium 280 < 1400M2, Large 1400 < 2800M2, Extra-large >2800M2), the higher the final score the better accessibility in that region.

Results showed that frequency of food outlets across Wales varied by region and showed an overall disproportionate number of supermarkets in relation to population density, a dominance of small supermarkets in combination with low numbers of large supermarkets creates a disadvantaged food environment where close proximity to healthy affordable food is limited [3]. The lowest scoring regions included Merthyr Tydfil, Blaenau Gwent and Torfaen, all areas of high deprivation [4].

The presence of an inequitable food environment is also seen within other parts of the UK [5, 6], improving the quality of the food environment within a community is not only positively associated with improved diet [7-9] but research has shown that choosing to locate supermarkets within a deprived area can lead to other positive associations such as improved social connections, job opportunities and increased pride in the local area [10].

References

1. Wrigley, N., ‘Food deserts’ in British cities: policy context and research priorities. . Urban Studies, 2002. 39(11): p. 2029-2040.

2. Caspi, C., et al., Pricing of Staple Foods at Supermarkets versus Small Food Stores. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2017. 14(8): p. 915.

3. Ghosh-Dastidar, M., et al., Does opening a supermarket in a food desert change the food environment? Health Place, 2017. 46: p. 249-256.

4. Macintyre, S., Deprivation amplification revisited; or, is it always true that poorer places have poorer access to resources for healthy diets and physical activity? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 2007. 4(1): p. 32.

5. Ellaway, A. and S. Macintyre, Does where you live predict health related behaviours?: a case study in Glasgow. Health Bull (Edinb), 1996. 54(6): p. 443-6.

6. Wrigley, N., D. Warm, and B. Margetts, Deprivation, diet, and food-retail access: Findings from the Leeds ‘food deserts’ study. Environment and Planning A, 2003. 35(1): p. 151-188.

7. Hood, C., A. Martinez-Donate, and A. Meinen, Promoting healthy food consumption: a review of state-level policies to improve access to fruits and vegetables. Wmj, 2012. 111(6): p. 283-8.

8. Karpyn, A., C. Young, and S. Weiss, Reestablishing healthy food retail: changing the landscape of food deserts. Child Obes, 2012. 8(1): p. 28-30.

9. Rose, D., Access to healthy food: a key focus for research on domestic food insecurity. J Nutr, 2010. 140(6): p. 1167-9.

10. Cummins, S., Large scale food retailing as an intervention for diet and health: quasi-experimental evaluation of a natural experiment. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 2005. 59(12): p. 1035-1040.